On the surface, ad blockers might seem like a reeeeally bad thing for Google. 76% of its revenue comes from ads, totalling $264BN in 2024. Any material threat to this would dramatically affect its prospects.

Despite the widespread rise of ad blocker usage over the past 15 years — whereby more than 1 billion users are now reported to be using ad blockers — Google has prospered financially under this circumstance.

Actually, you could make the case that it’s thrived. That it’s the single biggest benefactor from the rise of ad blocking. And, that recent moves in this area have further entrenched its unique competitive position.

How could that be?

How could the world’s most prolific purveyor of advertising fair so well?

Origin Story

It all started with Chrome. From 2009 it allowed extensions. Ad blockers, for obvious reasons, became the most popular type to install. There were two in particular that grew to dominate the early market for ad blocking: AdBlock and Adblock Plus.

Together, they controlled around 85% of the market by 2015. Which, by that point, had made the leap from early adopters to the mainstream — counting around 200M users. This growth was symbiotic with Chrome, riding its rise from a user-friendly challenger browser to global domination. It became the main platform for ad blocker usage.

Due to its unique view, Google was relatively early in spotting the rise of ad blockers and the threat it posed to ad supported business models. So, it took steps to mitigate their impact.

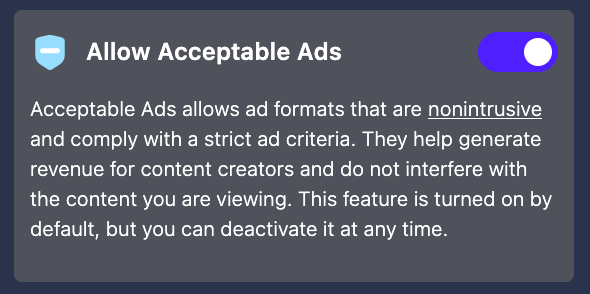

Fortunately for them, eyeo, the owner of Adblock Plus, launched an offering in 2011 in which publishers and advertising vendors could pay to whitelist their ads so that they’re exposed to Adblock Plus users. This offering, still running today, is known as Acceptable Ads and requires that certain ad criteria be met.

In 2013, Google joined the program to have its search ads whitelisted. This instantly recovered around 50% of ad blocker inventory, because Adblock Plus represented around 50% of ad blocker users at that time.

In 2015, the primary competitor of Adblock Plus — AdBlock — adopted the Acceptable Ads program (reportedly, because it was acquired by eyeo). When this occurred, Google’s search ads could reach the vast majority of ad blocker users.

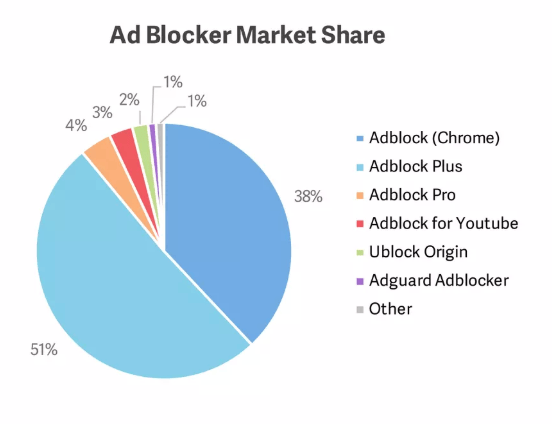

A Sourcepoint report from this time estimated that AdBlock and Adblock Plus together controlled 89% of the market:

This was a huge win for Google.

It paid a nominal fee (from its perspective) to restore the most lucrative ad product in its business. A payment of millions to receive billions.

If you were to spin this deal out as a separate business, it would be one of the largest advertising companies in the world.

From eyeo’s accounts, you can get a sense of how much the Google fee was by the amount of revenue it recorded. It would have represented a big chunk of the figures you see below:

Year | Revenue (Euros) |

|---|---|

2014 | €4.8M |

2015 | €39M |

Notice the jump in 2015? This is when Acceptable Ads could boast a nearly 90% coverage of ad blocker users.

This arrangement was particularly advantageous for Google:

Acceptable Ads criteria was strict when is started. Search ads complied, locking out the majority of Google’s competitors whose offerings depended on ad formats that did not comply.

The value of search ads under Acceptable Ads was very similar to non-ad blocker users. For Google’s competitors who were able to whitelist ads, it was not. Often, their ad inventory value would drop dramatically (up to 95%) due to the Acceptable Ads criteria, which was unfavourable to their propositions.

The main reason for Google’s commercial advantage over this time is the type of ad inventory (search) and its dominance over it.

Most of the value of search ads comes from the timing and context of search queries: consumers actively looking to buy stuff. These ads are “native” to the intention of the consumer in that moment, meaning they are both welcomed by consumers (relevant & non-intrusive) and high-value to advertisers (in-market buyers).

Conversely, many other forms of advertising offered by Google’s competitors did not fit this description so precisely, which also meant their offerings didn’t align with the Acceptable Ads criteria — it was closely aligned with Google’s.

To comply, their ad implementations had to be altered. Which, eroded their relative performance versus Google’s ads further. This is still the case today.

As Jason Kint, CEO of Digital Content Next, noted: the criteria for Acceptable Ads generally trended towards formats where Google had been and is still strong. It was also able to preserve user data collection to leverage this value further:

From a revenue growth perspective, the Acceptable Ads deal made total sense for Google.

By 2015, ad blocking rates were reported to be at levels that would pose serious financial harm to Google’s search ads business. Recovering these ad impressions and the user data associated with it was a massive bullet dodged.

But, just as significantly, it further advanced Google’s rising monopoly power over search and Internet advertising generally. Advertisers could achieve better outcomes for their campaigns than going to competitors, because Google could reach <20% of users they couldn’t, in advertising formats that were much more effective.

More addressability, more conversions, more business results.

Example?

Let’s pretend its 2014.

You're using Adblock Plus on Chrome and you’re in the market for a new pair of headphones.

You Google: “best headphones”

Here’s what happens:

Top of the search page: search ads for headphones

Below the search ads: links to headphone reviews on gadget websites

You click-through to a review: on TechRadar, comparing Beats headphones

On TechRadar: no ads load for headphones because they’ve been blocked

Back to Google: you search “Beats Studio” because this model sounds cool

Top of search page: search ad for Beats Studio on BestBuy.com appears

You click the ad link: make the purchase on BestBuy.com

Do you see what happened there?

TechRadar, and its advertising partners, were unable to serve an ad for Beats Studio headphones. Google was able to serve an ad, and they delivered the converting lead to the advertiser.

This is a significant strategic advantage. It makes the overall proposition of Google’s advertising services so much stronger.

This is no small point.

It’s not just the value of reaching ad blocker users that matters here (which is compelling enough as an incremental addressability pitch). It’s also the value of having a “one stop shop” for advertisers to reach everybody. Which, is a central pillar supporting Google’s dominant market power.

Advertisers prioritise budget allocation to channels where they see the greatest volume of perceived cost effective outcomes. The Acceptable Ads whitelisting advanced this materially.

Anti-Trust Vibes

Now, if you are the DOJ and you see the world as they do, this may smell a little fishy.

If you probe further, it smells even more fishy.

More context you’ll find:

The non-search advertising ecosystem that Google helped facilitate around the web through its other non-critical revenue products and YouTube encouraged the adoption of ad blockers — high-saturation, distracting ads

Chrome played a key role actively promoting AdBlock and Adblock Plus and driving up their respective user bases

Google reportedly paid (and still is) a much lower whitelisting fee to eyeo than its competitors — 1-2% versus 30%

Eyeo taking Google’s tens of millions in fees and funding the growth of its user base that further advantaged Google and disadvantaged Google’s competitors

Eyeo auto-opting users into Acceptable Ads and not being upfront enough with consumers about the fact its ad blockers show ads for its financial benefit

A sceptical view might conclude this was orchestrated by Google. With eyeo playing a willing accomplice.

It all seems very “convenient”.

After all, executives at Google likely concluded they couldn’t ban ad blockers from Chrome. That could have jeapordised Chrome’s adoption, which at that point had a sub-40% market share and was growing up and to the right.

However, ad blocking was threatening the search ads golden goose.

They *had to* do something about it.

Another option? Partner with commercially-minded ad blockers to achieve Google’s strategic business objectives. Grow together to build dominance in each’s respective markets.

What you end up with is this growth loop:

In a nutshell: Google pays a third-party company (eyeo) to either block or severely devalue it’s competitor’s ad products, preserving its own.

Meanwhile, it provides the platform for eyeo to grow its ad blocking extensions via Chromium; the Google-controlled open source browser project utilised to build Chrome, Edge, and others (representing a 75%+ market share).

Even Firefox, an outlier that doesn’t use Chromium, uses Chromium’s extension framework. It has to do this, otherwise it can’t compete with Chrome. Meaning, it bends to Google’s will — doubly so given that Firefox’s existence is funded by Google.

Now… to suggest that this was all a grand design does feel a bit tin foil hat.

Sure, these things happened. But, I don’t buy that it was all a master plan. Even in light of the anti-trust shenanigans that have surfaced from the DOJ drama — some of which were very much by design.

Ultimately, this ad blocking situation feels like an inevitable consequence of Google’s lucrative search ads business, which enabled it to fund a push into every corner of the Internet that touched ads. The second order affects of this are naturally going to create a lot of dynamics that unfairly (or not) privilege its own business — helped by a few deliberate nudges along the way.

But, we needn’t dive in anymore here on that. What matters, by design or not, is the affect it had.

Google became the main individual benefactor of ad blocking, by advancing its market power and avoiding the relative financial hit that the rest of the browser-dependent digital ad ecosystem had inflicted upon them.

However, this is not the end of the story!

That was then. It’s 2025.

Things have moved on over the last decade. The ad blocking ecosystem has evolved into something quite different: more ad blockers, more methods of ad blocking, and more ad blocker users.

Google still finds itself in a comfortable spot — and things smell even fishier.

Did you expect anything else?

What’s Happening Now

Let’s start with eyeo. Google still pays to have its ads whitelisted under Acceptable Ads. That amounts to 400M users, according to eyeo.

The main difference today is that Acceptable Ads users represent less than 30% of total ad blocker users (reason why here).

Meaning: if Google relied on this alone to serve search ads to ad blocker users it would be leaving 70%+ on the table. That’s equivalent to 700M+ users (more than 3X the amount it was reaching via Acceptable Ads in 2015). Big numbers, even for Google.

So, what’s happening with this 70%? Where does Google reach users through Acceptable Ads?

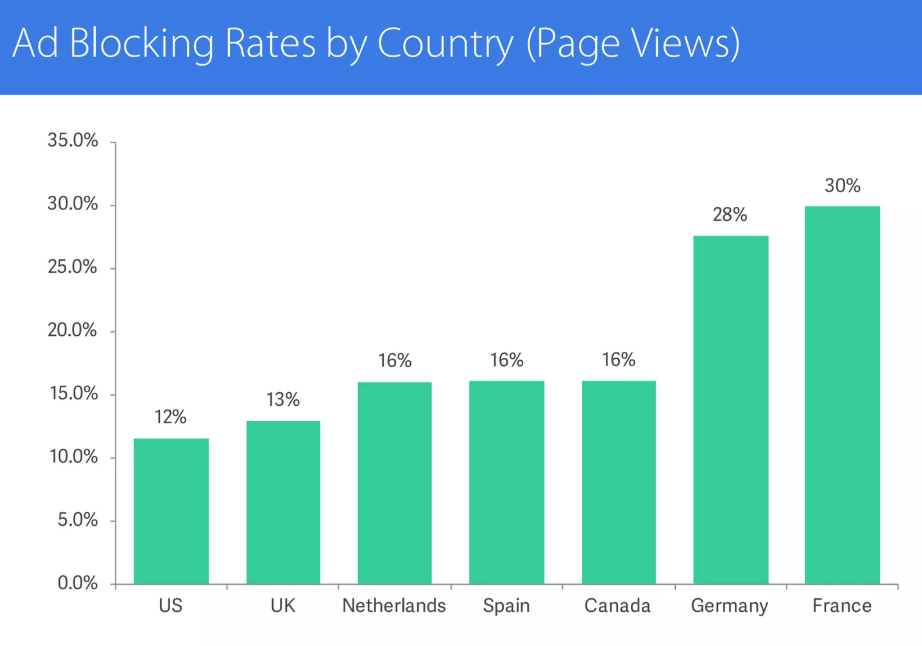

First, we need to breakdown what the ad blocker ecosystem looks like today. It has fragmented into different types of ad blocking across a variety of products.

There’s:

🧩 Browsers with ad blocking extensions

e.g. uBlock Origin, Pie

🖥️ Browsers with built-in ad blocking

e.g. Comet, Brave

🔒 VPNs

e.g. Surfshark, NordVPN

📱Apps (iOS, Android, etc)

e.g. AdBlock Pro, Adblock Fast

🌐 Network-level

e.g. NextDNS, custom IT setups

All of these have large user bases, each.

🧩 Browsers with ad blocking extensions

Estimated users: <300M

First, let’s take a look at the OG type of ad blocking: browser extensions.

Chrome (market share: 69.6%)

Chrome remains the dominant force in ad blocker extensions.

AdBlock and Adblock Plus still have huge user bases, but they are far from the only game in town. There are now hundreds of ad blocking extensions available.

Up until recently, it looked like this amongst the 5 most popular:

Extension (Chrome) | Users (Chrome Store) | Acceptable Ads? |

|---|---|---|

AdBlock | 58M | Yes |

Adblock Plus | 38M | Yes |

uBlock Origin | 30M | No |

AdGuard | 14M | No |

Adblock for YouTube | 9M | No |

Those that are bolded in green show Google’s search ads (they do not block them) at the time of testing (4/5).

AdBlock and Adblock Plus do so because of Acceptable Ads. AdGuard because it’s a “policy” (that Google’s adtech competitors are not privilege to).

And, Adblock for YouTube? Not sure. It claims to block all ads ¯\(ツ)/¯

Looking at this you can draw two basic conclusions:

Overall, this is a win for Google

uBlock Origin is a problem

Well, actually, that’s not true anymore.

Put a peg on your nose, because it’s gonna start to smell fishy again!

uBlock Origin is no longer blocking search ads. Due to a browser update that Google recently pushed through, it has been removed from Chrome. Poof… gone just like that.

So, what are these 30M ex-uBlock Origin users doing now? A small segment have ditched Chrome for other browsers like Brave and Comet. Others won’t have noticed, frankly.

But, you know what a big chunk are going to do? Probably, the vast majority? They’ve been looking for new ad blocking extensions. And, guess what happens when you head to the Chrome Store and search for “ad blocker”?

You get recommended a bunch of ad blockers.

Of these:

The no.1 and no.2 results show Google's search ads

4/6 results show Google’s search ads (highlighted with a blue border)

Guess what’s missing? uBlock Origin Lite.

It’s the closest replacement to uBlock Origin, made by the same developer. It also happens to block Google’s ads.

It did not appear in the first 50 results (I gave up looking for it at this point), despite the fact it has 8M users and a review rating of 4.5 stars — making it one of the most popular and highly-rated on the Chrome Web Store.

Due to uBlock Origin’s removal, the “new top 5” most popular ad blocking extensions on Chrome are now:

Extension (Chrome) | Users (Chrome Store) | Acceptable Ads? |

|---|---|---|

AdBlock | 58M | Yes |

Adblock Plus | 38M | Yes |

AdGuard | 14M | No |

Adblock for YouTube | 9M | No |

uBlock Origin Lite | 8M | No |

Again, this is all very “convenient”.

You can draw your own conclusions.

Bottom-line: Google is doing OK on Chrome when it comes to serving search ads to ad blocker users. The most popular show them, including those that are not part of Acceptable Ads — such as AdGuard.

Having said that, there is a long-tail of ad blocking extensions that do no show search ads. Some of these have meaningful user bases, such as: Ghostery (2M), Pie (2M), Stands (2M), and AdBlocker Ultimate (1M).

What about extensions on other desktop browsers?

Google is fairing well there, also.

Let’s have a quick look:

4/5 of the most popular ad blockers show Google search ads.

Not only that, but they represent the vast majority of ad blocker extension users on Edge. Of course, this will only impact the 30-40% of Edge users that use Google to search (the remainder use Bing, the default search engine in Edge).

Extension (Edge) | Users (Edge Add-Ons) | Acceptable Ads? |

|---|---|---|

AdGuard | 10M+ | No |

AdBlock | 10M+ | Yes |

Adblock Plus | 10M+ | Yes |

uBlock Origin | 10M+ | No |

Adblock for YouTube | 1M+ | No |

You will notice uBlock Origin is strong here, with 10M+ users. This is not going to last. Because Edge is built with Chromium (owned by Google), it will be adopting a browser update that will render uBlock Origin incompatible and force its deactivation. This is the same browser update that forced it out of Chrome, called Manifest V3.

3/5 of the most popular ad blockers show Google search ads. The no.1, uBlock Origin, does not. There’s a reason it dominates here: Firefox is like the unofficial home of the most ardent uBlock Origin fans.

Overall, the numbers blocking search ads are relatively low. It does not represent a major cause of concern for Google.

Extension (Firefox) | Users (Firefox Add-Ons) | Acceptable Ads? |

|---|---|---|

uBlock Origin | 9.5M | No |

Adblock Plus | 3M | Yes |

AdGuard | 1.4M | No |

AdBlocker Ultimate | 1.4M | No |

AdBlock | 1.2M | Yes |

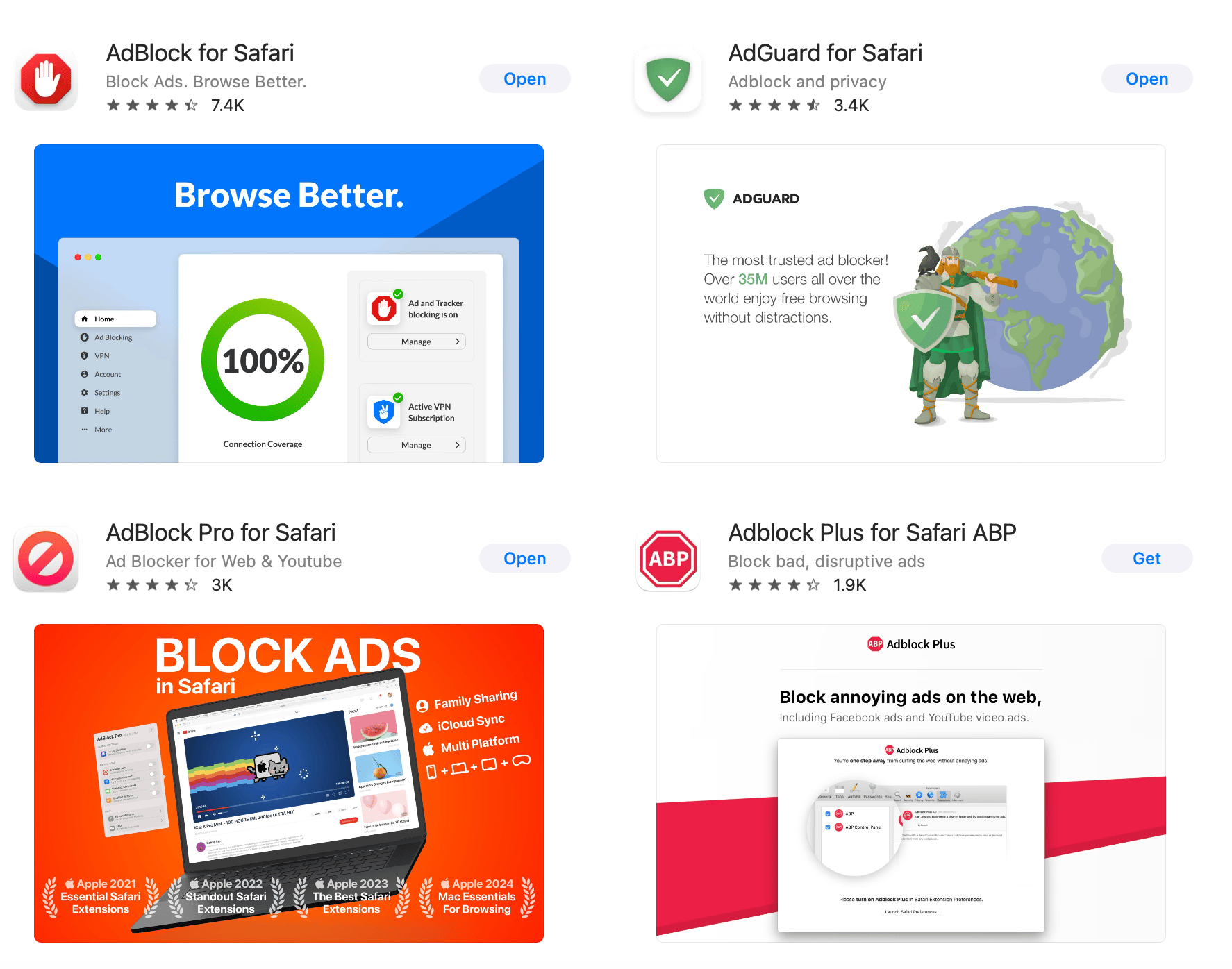

It’s a similar story for Safari: 3/4 of the most popular ad blockers show Google search ads. The exception being AdBlock Pro for Safari:

What about mobile browsers?

Extensions do not really exist on mobile browsers. Instead, there’s apps known as “content blockers” that integrate with browsers such as Safari and Samsung Internet to block ads, like an extension equivalent. The user base for these is not huge, despite the phone market being huge (they are awkward to install).

Among the most popular are AdGuard, Adblock, and Adblock Plus. They all show Google search ads. More on this later.

ℹ️ Takeaway: Search ads reach more than 75% of browser extension ad blocker users

🖥️ Browsers with built-in ad blocking

Estimated users: <300M

There are lots of browsers out there vying to take on Chrome. Many of them have built-in ad blocking to differentiate themselves from it, because that’s something Google isn’t prepared to do more than a token amount.

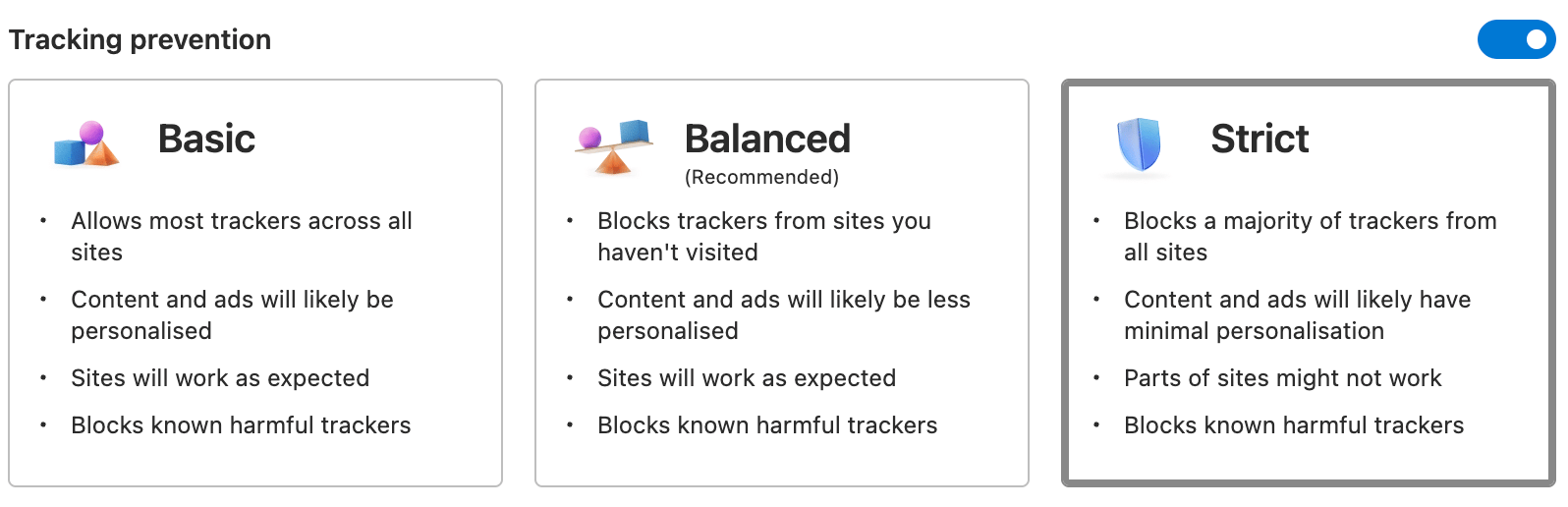

Microsoft Edge

The most widely used browser with a comprehensive built-in ad blocker is Edge. However, this has to be manually turned on — meaning <5% of its user base likely has it on. This would amount to <20M users.

However, this doesn’t matter for Google’s search ads. The feature does not block them.

“Strict” mode in Edge blocks most ads

Acceptable Ads browsers

There are a number of browsers that have Acceptable Ads built-in (meaning Google search ads will load if this is activated). The most notable being Opera, Aloha, and Adblock Browser. Collectively, they have around a 2% market share. Opera makes up the vast majority of this with 250-300M users — Acceptable Ads is turned on by default when ad blocking is activated.

Google’s OK here.

Acceptable Ads is on by default in Opera browser.

Privacy Browsers

There are many browsers that position themselves as the antidote to Chrome: private and ad free. Many of them are built with Chromium. Only a few have more than a few million active users. Examples:

Browser | Users | Acceptable Ads? |

|---|---|---|

Brave | 93M | No |

DuckDuckGo | 50M+ downloads (likely <10M users) | No |

Vivaldi | 3.5M | No |

As you can see, search ads are not blocked with three of the most popular.

However, Google is not set as the default search engine on any of these browsers.

As I mentioned earlier, around 30–40% of Edge users switch their default search engine to Google. If we apply this same ratio to the browser user numbers above, we can estimate Google's potential reach for search ads on these platforms. In other words, roughly one-third of the users of these browsers are exposed to Google’s search ads (36M).

There’s also Tor Browser and LibreWolf, which are essentially fork projects of Firefox’s Gecko engine. These browsers are used by hardcore privacy and ad blocking aficionados, and have small user bases that’s likely low single digit millions. They’re inconsequential for Google.

Overall, Google search ads are minimally impacted by privacy browser ad blocking.

AI browsers

Arguably, the biggest threat to search ads is AI browsers — or “agentic browsers”.

Such browsers are likely to block ads comprehensively because the type of early adopters that want to use AI browsers are also generally ad blocker users. It’s a table stakes feature for them.

Not only that, but the nature of the way they work could make Google’s search engine redundant. Users don’t go to a search bar anymore, they chat with the browser. And, further: the companies building these browsers have an incentive to nudge out Google, so they can layer in their own ad infrastructure and dominate that business model.

So far there is one main contender in this emerging category, Comet (by Perplexity). It has built-in ad blocking. But, it does not remove search ads. Google gets a pass here, again (for now).

OpenAI’s browser will follow soon. Expect it to have built-in ad blocking, too.

The user base of AI browsers is currently tiny — but that could change quickly.

Comet’s built-in ad blocker

ℹ️ Takeaway: Search ads reach more than 75% of built-in browser ad blocker users

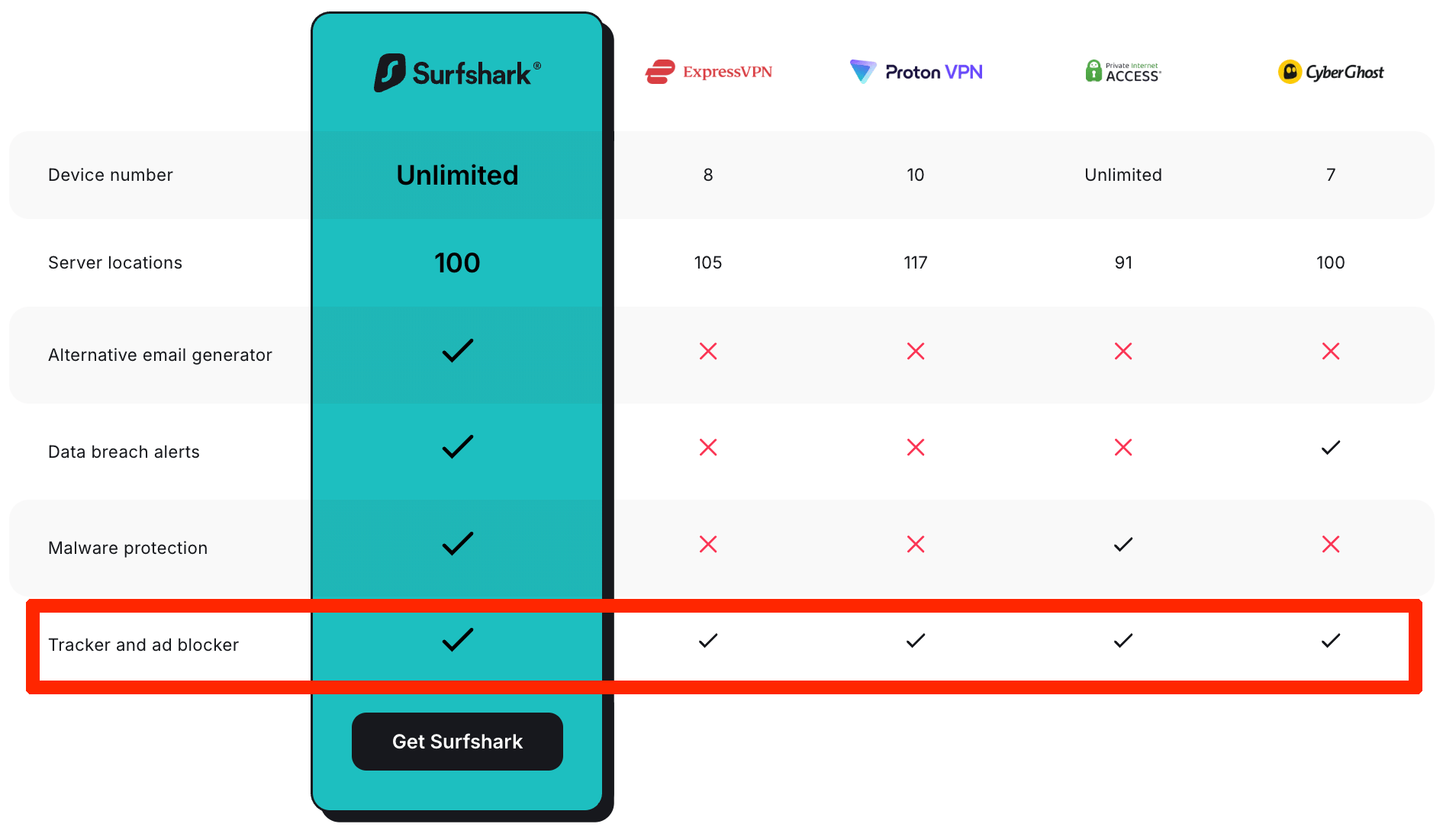

🔒 VPNs

Estimated users: <100M

VPNs like Surfshark, NordVPN, ExpressVPN, and ProtonVPN now offer ad blocking as part of their feature set. In fact, its becoming standard.

These tools operate at the network level by blocking requests to known ad domains using public blocklists such as AdAway. They are therefore effective at removing most ads across the web, because most ads are served by calling a domain dedicated to ad serving purposes.

A major exception to this?

You guessed it, Google’s search ads. These are able to load for VPNs.

Why?

If an ad is delivered from the same domain as the website you are visiting, it is unable to be blocked by the method used by VPNs. The website (e.g. google.com) would get blocked along with the ads. This is known as serving ads “first-party”. Google serves search ads through this methodology.

It does also use third-party domains — e.g. googleadservices.com — in support of serving ads as well. But, it starts to get messy trying to block it. Stuff breaks.

In other words, this is ad circumvention.

It could also be the case that a VPN has made it an internal “policy” — like AdGuard — not to go after Google’s search ads. For example, some offer browser extensions that could hypothetically block search ads.

Right now, VPN ad blocking is mostly opt in. Because of this, the total user base of VPN-based ad blocking is lower versus other ad blocking methods. Likely, in the tens of millions.

In the future I will dig into this more, to get harder numbers around what is happening. Some VPNs may have taken steps to block search ads. The current VPN I have installed — ExpressVPN — does not block search ads.

For today, we can conclude VPNs are not an issue for Google.

ℹ️ Takeaway: Search ads reach more than 75% of VPN ad blocker users

📱Apps (iOS, Android, macOS)

Estimated users: <100M

There’s many app ad blockers available across various platforms.

In this context, I am referring to “apps” as content blockers — standalone applications that integrate with browsers like Safari on iOS or Samsung Internet on Android.

These apps don’t block ads directly but provide filter lists and rules that the browser uses to hide or suppress ad content during page loads.

Like other methods of ad blocking, a few of them command the majority share of users:

App (Android) | Downloads | Acceptable Ads? |

|---|---|---|

AdGuard Content Blocker | 50M (est) | No |

AdBlock for Samsung Internet | 10M+ | Yes |

ABP for Samsung Internet | 10M+ | Yes |

Adblock Fast | 8M (est) | No |

Blokada | 4.4M (est) | No |

App (iOS) | Downloads | Acceptable Ads? |

|---|---|---|

Adblock Plus for Safari | 10M (est) | Yes |

AdBlock Pro for Safari | 10M (est) | No |

AdGuard | 10M (est) | No |

1Blocker | 4M (est) | No |

Total Adblock | <500K (users, est) | No |

There’s also apps for Windows, Mac, and other platforms. AdGuard tends to be the dominant force here, which shows search ads.

Overall, apps do not pose a serious problem to Google.

ℹ️ Takeaway: Search ads reach more than 75% of app ad blocker users

🌐 Network-level

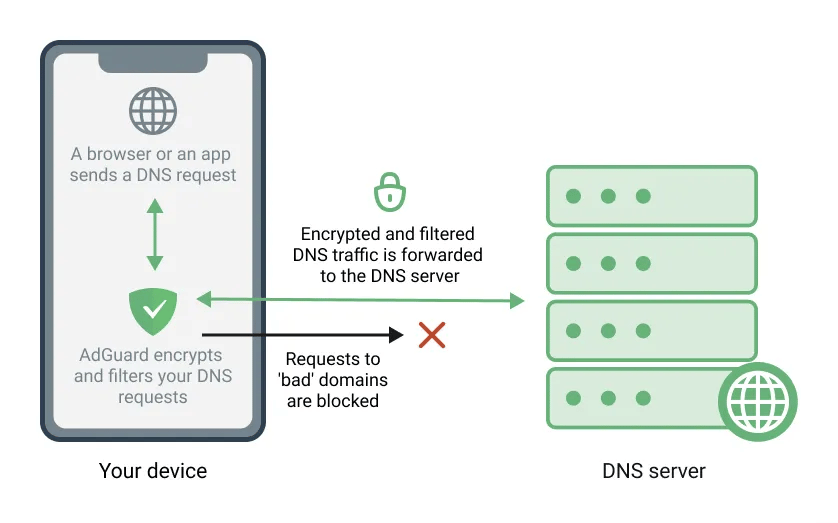

Estimated users: 350M+

Estimates suggest there are 350M+ users blocking ads via the network-level.

The methods to which network-level ad blocking is deployed vary.

Some apply public blocklists to personal DNS resolvers. Others use firewalls. Others use outbound web proxies.

DNS-based ad blocking is the most commonly used, offering the optimal combination of ease of setup and broad blocking effectiveness.

It works similarly to VPN-based ad blocking — both intercept dedicated ad domain requests and block known domains before they reach the browser. Google’s search ads will load much of the time, because they originate from google.com. Fastidious IT managers find ways to block it.

For the same reason, search ads also tend to load when ad blocking is built into firewalls, since those too rely on IP-level rules and DNS filtering.

Of the three, outbound web proxies (such as Squid with content inspection) are technically capable of blocking Google search ads, because they can analyse and filter the full content of web traffic — including first-party requests.

However, web proxies are rarely used in practice, as it introduces latency, requires significant configuration and maintenance, and can break secure (HTTPS) connections without complex certificate handling.

ℹ️ Takeaway: Search ads reach more than 75% of network-level ad blocker users

Bottom Line

There are over 1 billion ad blocking users globally. Google is reaching the majority of them with search ads — likely more than 75% (750M+).

It has achieved this via:

Paying to be whitelisted (via Acceptable Ads)

Circumventing ad blockers (deliberately, or not)

Finding itself on the favourable side of ad blocker “policies”

Ad blocking type | Search ads served - reaching 75%+ users |

|---|---|

🧩 Browsers with ad blocking extensions | ✅ |

🖥️ Browsers with built-in ad blocking | ✅ |

🔒 VPNs | ✅ |

📱Apps (iOS, Android) | ✅ |

🌐 Network-level | ✅ |

Adblock Analyst View

Google has turned what could have been an major financial hit into a competitive advantage. While the rest of the digital advertising ecosystem has hemorrhaged hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue to ad blockers, Google's search advertising business remained largely intact.

The advantage went beyond simply maintaining ad delivery through Acceptable Ads, first-party ad delivery, and receiving preferential treatment from ad blockers like AdGuard.

Ad blocking has actively removed or devalued competitors’ ads, making its own uniquely valuable. This gave Google’s ad products a structural edge in relative performance. It could reach more target customers, more consistently, and more effectively than anyone else.

Whether or not this will continue, remains to be seen. Keep a close eye on AI browsers, VPNs, and ad blocking extension & browsers installed at an organisational-level (more on that in a follow up newsletter!).

Adblock Analyst

Breaking down the business of the ad blocking ecosystem.

Don’t miss a beat. Subscribe below.